The First Stewards: 12,000 Years of Kumeyaay History

Long before Spanish ships arrived or modern maps were drawn, the Kumeyaay people lived in La Misión. To understand how long they’ve been here, consider this: when the ancient Egyptians were just starting to build the first pyramids, the Kumeyaay had already lived in Baja for over 7,000 years.

A Name Based on the View

The name Kumeyaay (or Kumiai) basically means “those who face the water from a cliff.” If you’ve ever stood on the tall bluffs overlooking Playa La Misión, you’ve seen exactly what they saw. Their land was huge, stretching from San Diego all the way south to Ensenada and east to the Colorado River.

They Weren’t Just Living in Nature—They Were Managing It

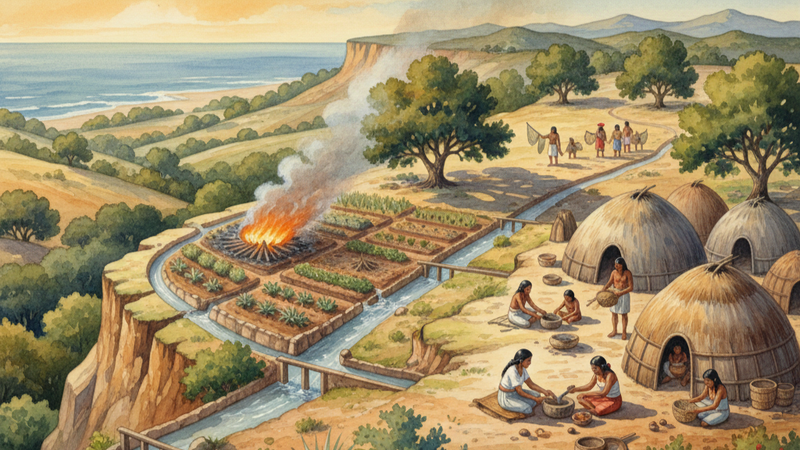

A common mistake people make is thinking that indigenous groups just “wandered around” looking for food. The Kumeyaay were actually expert environmental engineers. They didn’t just take what the land gave them; they improved the land using techniques we are still studying today:

- Controlled Burns: They intentionally set small fires to clear out dead brush. This prevented massive wildfires and helped new plants grow, which attracted deer and rabbits for hunting.

- Water Engineering: They built small dams and terraces in the hills to slow down rainwater. This stopped the soil from washing away and kept the ground moist for growing grains.

- The First Farms: When Spanish explorers first saw the lush green valleys of California, they thought it was “wild” nature. In reality, they were looking at massive, carefully managed grain fields planted by the Kumeyaay.

Moving with the Seasons

The Kumeyaay didn’t stay in one spot all year. They used a system called seasonal movement. In the summer and fall, they moved into the mountains where it was cooler to harvest acorns and pine nuts. In the winter, they moved down to the coast to fish and collect shellfish while the weather was mild. This gave the land time to heal and regrow every year.

The Kumeyaay “Supermarket”

The Kumeyaay diet was incredibly healthy and diverse. Their most important food was the acorn. Women would gather acorns by the thousands, grind them into flour using heavy stones, and make a nutritious mush called shawii. They also ate chia seeds, cactus fruit, wild onions, and seafood. They knew exactly which plants could be used for food and which were medicine.

Science and Culture

The Kumeyaay were skilled astronomers. They used stone markers to track the stars and the sun. This “rock calendar” told them exactly when the seasons were changing so they knew when to move camp or plant seeds. They also have a musical tradition called Bird Songs. These songs are like oral history books, telling the story of the people and how to treat the earth with respect.

A Difficult History

When Europeans arrived, life changed drastically. The Mission system forced the Kumeyaay to stay in permanent settlements. New diseases like smallpox killed up to 90% of their population. It was a devastating time that almost wiped out their way of life.

The Kumeyaay Today

Despite these hardships, the Kumeyaay are still here. Today, descendants in Baja and Southern California are keeping their language alive, teaching traditional basket weaving, and working to protect sacred sites and ancient artifacts.

Why It Matters to You

When you hike the trails or walk the beach at La Misión, you are walking through an ancient home. If you see a smooth, bowl-shaped hole in a rock, that’s a bedrock mortar where someone ground acorns hundreds of years ago. The Kumeyaay prove that humans can live in a place for 12,000 years without destroying it. They remind us that if we take care of the land, the land will take care of us.