Rancho Days: Family Roots and Cattle Country (1862–1938)

After the mission bells fell silent in 1834, La Misión entered a quieter but equally important chapter. This was the era of the great ranchos—a time when families established deep roots, cattle replaced mission livestock, and the region began to transform into the place we recognize today.

The Gap Years (1834–1862)

Between the mission closing and the first big rancho, the land was in a state of “limbo.” In 1848, the Mexican-American War ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This treaty moved the border just a few miles north of La Misión. While California became part of the United States, Baja California remained part of Mexico. This made La Misión a true frontier town, sitting right at the edge of two different countries.

Enter the Crosthwaites: 1862

In 1862, a man named Felipe Crosthwaite Armstrong changed the history of the area forever. Felipe was a Mexican citizen of Irish descent—a perfect example of the “melting pot” of cultures in 19th-century Baja. He purchased about 18,500 acres of old mission land from the government and named it Rancho La Misión Vieja de San Miguel.

To give you an idea of the size, his ranch covered roughly 29 square miles! It stretched from the coast all the way into the eastern hills, including the entire valley where the river flows today.

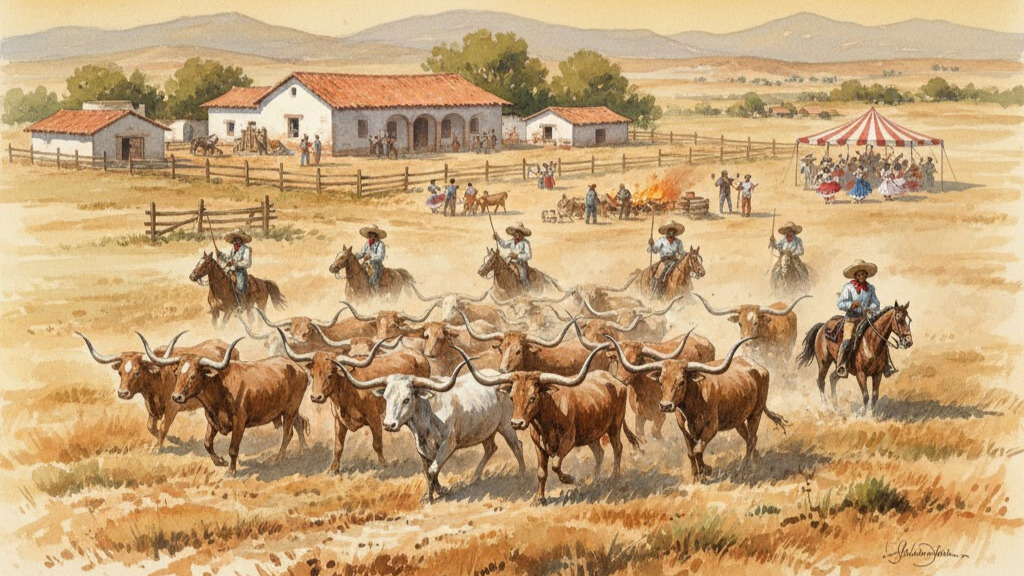

The Vaquero Culture

The ranch was primarily cattle country. This was the golden age of the vaquero—the Mexican cowboy. These riders were famous for their incredible horsemanship. In fact, the American word “buckaroo” actually comes from the word “vaquero.”

Life on the ranch followed the seasons:

- Spring: Calving season and moving herds to fresh grass.

- Summer: Driving cattle to markets.

- Fall: Roundups and branding the cattle with the family mark.

- Winter: Repairing gear and preparing for the next year.

This era also gave birth to the Baile Calabaceado, a high-energy folk dance inspired by the movements of cowboys. You can still see this dance performed every year at the Fiesta en La Misión!

Daily Life on the Ranch

The ranch was like a small, self-sufficient village. The main house was built of thick adobe bricks and surrounded by stables, a blacksmith shop, and homes for the workers.

While the men worked with cattle, the women managed the households, preserved food, and often kept the ranch’s financial records. Children started helping with chores by age seven or eight, learning the skills they would need to run their own ranches one day.

The Crosthwaite Legacy

What makes the Crosthwaite story amazing is that the family is still here. Over 160 years later, descendants of Felipe Crosthwaite still live in La Misión. In a world where people move around constantly, this family has stayed through revolutions, border changes, and modern growth. Their presence is a living bridge to our past.

Land and Inequality

While ranch life sounds romantic, it had a darker side. A few powerful families owned almost all the land. The workers (vaqueros and laborers) usually owned nothing. They lived on the ranch and were paid small wages, often remaining in debt to the “company store.” This gap between the rich landowners and the poor workers eventually led to the Mexican Revolution in 1910, as people across the country demanded “Tierra y Libertad” (Land and Liberty).

The Transition to the Ejido

By the 1930s, the era of the giant private ranchos was coming to an end. To fulfill the promises of the Revolution, the Mexican government began breaking up these massive estates to give land back to the people. In 1938, much of the Crosthwaite ranch was redistributed to create Ejido La Misión. This allowed local workers to own and farm the land as a community, which is how much of the valley is still organized today.

Why the Rancho Era Matters Today

The ranching days left a permanent mark on La Misión:

- Agriculture: The ranchos improved irrigation and figured out which crops grew best in our specific soil.

- Tradition: The music, cowboy skills, and dances we celebrate today started on these ranchos.

- Identity: The sense of “rootedness” and family pride in La Misión comes directly from these early pioneers.

The rancho period was the bridge between the old mission days and the modern community we live in today. It was a time of hard work, skilled horsemanship, and the beginning of the local families that still call La Misión home.